A personal global alphabet: C is for Cappadocia

Travel back thirty years in this latest installment of memories and misadventures from around the world

Rosemary and I met in early 1991, got married in summer of 1992 and in 1994 decided it was time to start a family, so we wanted to do one adventurous – yet affordable – trip before the long years of tight budgets and no free time. We settled on a circle through Turkey. It didn’t disappoint.

We had a sleeper car for the train across Asian Turkey. The train left the station on the east side of the Bosphorus after sunset and climbed in darkness up to the Anatolian plateau. In the morning, I awoke to a high, dry plain, across which silks and spices were carried in caravans for a thousand years. I convinced myself the scene looked as remotely Central Asian as something I might have glimpsed on the Silk Road between Samarkand and Mongolia. We were on our way to Cappadocia, easternmost province of the Roman Empire.

After a change from train to bus in the capital, Ankara, we arrived in the village of Goreme, a community built amid the bizarre rock pinnacles and canyons for which Cappadocia is famous. The volcanic material of these rocks is light and soft, which has allowed people to carve out entire villages of rock-walled and rock-floored houses, churches and stables. Our hotel, in fact, consisted of a scattering of such rocks, each carved into one or two rooms. Sleeping in a man-made cave turned out to be restful and cool in the June heat.

Upon arrival, our hotel’s owner gave us a map she had made of the network of local trails, some no doubt in use since Biblical times. The trails connected communities and farms and took us through narrow slot canyons, up ladders carved in the rock, through orchards and past gardens. Everywhere we went we saw houses with their roofs covered in apricots, drying in the sun. We bought the golden dried fruits from roadside stands and they were delicious, though I never did find out how they keep the apricots from being covered in bird droppings.

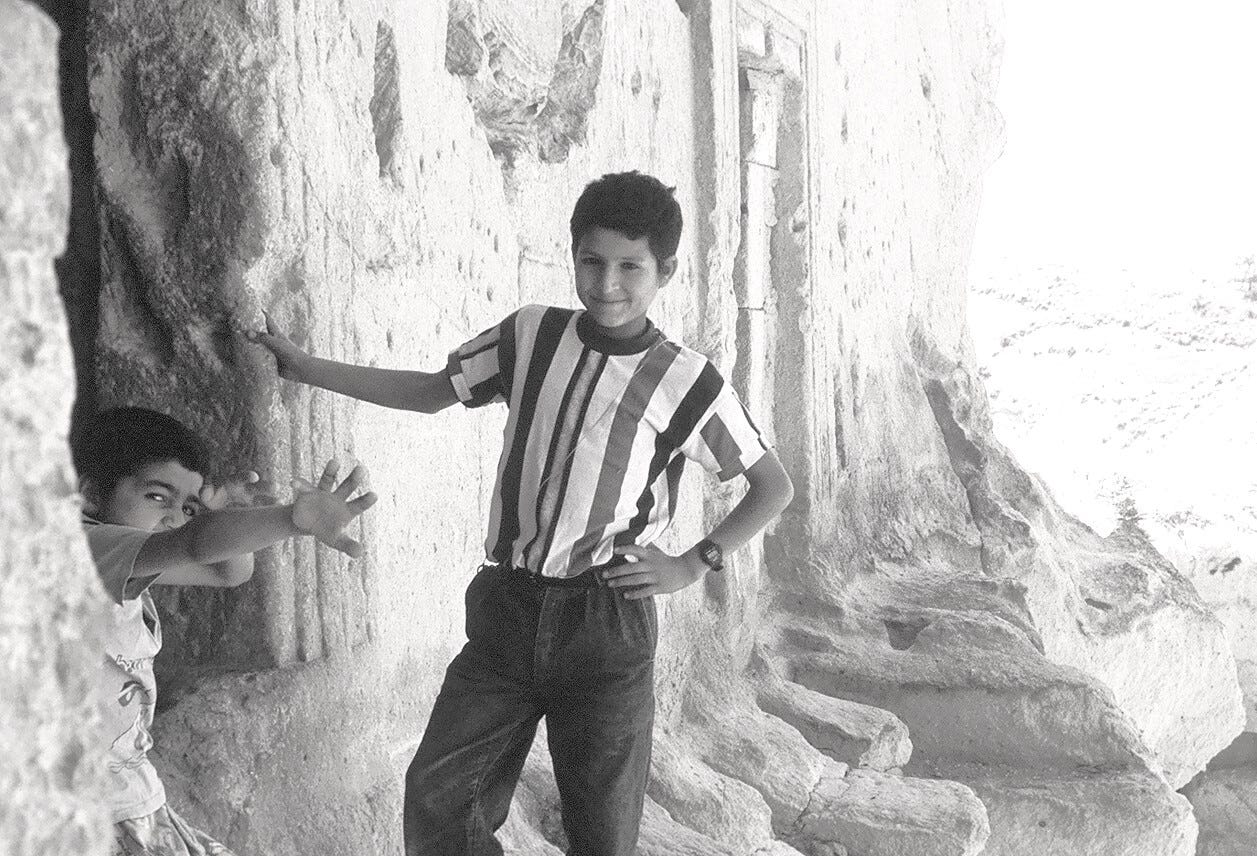

On one day’s walk, we caught a ride back in a farmer’s horse-drawn wagon. Another day we visited a large outcropping that had long ago been carved into a kind of stone apartment building. Here we were set upon by local children wanting to be our guides for the day. We didn’t really need guides. I had somehow acquired the idea that it was very bad for tourists to give in to begging, if that’s what this was, and had read that it would be a good idea to bring school supplies, toys or souvenirs from home to give to kids like these, instead of money. (Yes, I realize it was extremely patronizing of me to take upon myself the responsibility of not spoiling kids from a much poorer country.) The souvenirs I brought – packages of hockey cards – elicited only puzzled expressions. The toys – little plastic parachutists – were much better received. Shamed by the dismayed expression on one of our “guides,” we added a bit of cash.

Our last hike in Cappadocia involved a bus trip with a group of others to the Ihlara Valley, a narrow canyon whose walls had been carved into multi-story houses and churches. Several of the old stone churches had frescoes painted on the walls and in all of them the eyes had been scratched off, presumably after Christian Byzantine Empire had been conquered by the Turks, who brought with them Islam’s ban on depictions of the human form.

After Cappadocia, we took a bus to Cirali, a beach village on the Mediterranean, west of the city of Antalya. We had no reservations anywhere and found ourselves a cheap hotel which we very quickly thought better of. The Turkish squat toilet, in combination with the first cockroach sighting of my rather sheltered life, made us grab our packs and look for something else. At this point, a woman driving by stopped and asked us if we were looking for a place to stay.

“Well, sure, if you know a place.”

“I have a guest house. Very nice. Sima Peace hotel. Sima means peace. Come in, I lift you.”

She had a kind expression and something of a hippiesh look about her and reminded us several times of the meaning of “sima.” We ended up eating at her place and spending one night there. We were still in the mood for something a little more comfortable and recalled having seen a sign for a place called the Hotel Canada. Not very adventurous of us, perhaps, but we thought perhaps a place with a name like that would be clean and comfortable.

Turned out, we were right. In fact, it was managed by a Canadian/Turkish couple who lived part of the year in Calgary. We ended up staying there for the remainder of our time in Cirali.

We arrived with somewhat grandiose plans to hike in the mountains above the beautiful sandy beach, but those plans evaporated in the heat. We did walk to the Chimera – a series of burning natural gas vents in the rock at the east end of the beach. They’re most impressive at night. We learned when we went to see them that night is also when the scorpions in the area are out, so you definitely want closed-toe shoes when you check them out.

From Cirali, we took a bus along the Lycian Coast of Turkey, past Patara, home town of the original reindeer-free St. Nicholas, to the town of Fethiye. Here we planned to walk on ancient trails to a white sand beach called Olu Deniz. The trail took us along Roman cobblestone paths and then through an abandoned Greek village, emptied out by the ethnic cleansing that was part of the Turkish-Greek war that followed the First World War. I’d read in advance that at this point it was important not to be tricked into walking to the landing of an enterprising water taxi operator whose business model was luring hikers to his boat and then overcharging them for the ride to the beach.

I thought I was avoiding the boatman’s deceptive markings when we found ourselves descending to the landing. Damned if I’d give him the satisfaction of charging us for a ride, I thought. Much bushwhacking and route-finding followed, with Rosemary at one point suggesting she might just swim around the peninsula blocking our way to the beach. We kept at it, through a dry forest filled with spiny vegetation, and I made the mistake of mentioning that the region was also home to wild boars, which, like the scorpions near the Chimera, were also said to be more active at night. Fortunately, long before dark, we reached the proper trail and quickly found ourselves descending via a seldom-used trail to the popular swimming spot. How seldom used? Well, we came around a corner and surprised a couple in a very private moment.

After Fethiye we continued by bus along the coast highway to the city of Selcuk, a short distance from the Roman ruins at Ephesus (as in St. Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians). We arrived with time to gasp at the multi-storey façade of the Library of Celsus, exclaim over the beauty of the Great Theatre built into a hillside and pose for the obligatory photos in the ancient stone group toilet (where citizens used a common sponge on a stick to wipe themselves clean and where running water from the mountains above did the flushing for them). Somewhere in there we took photos of statues of Diana of Ephesus, a goddess endowed with a dozen breasts. It was a spectacular place and worthy of a second trip, which we planned for the next day.

The next day, Rosemary felt sick and decided to rest in the hotel in Selcuk while I went to the ruins. I had barely started walking down the main road of the ancient city when I felt several ominous rumblings. Not wanting to be forced to re-enact Roman history on that stone toilet, I made it back to the hotel just in time. We spent the rest of the day in a doped-up Gravol haze, sleeping when we could and trying to figure out what we had and how we’d acquired it. Our best guess was a roadside pizza that we’d bought on the long bus trip from Cappadocia to Cirali.

The illness subsided and recurred a few times over the remainder of our trip, with one nasty attack on the flight home, which I won’t horrify you with here. With the cramps, fever, occasional bouts of diarrhea and overall fatigue, I felt terrible. But also, in a strange way, proud. When I’d been younger and dreaming of a globe-trotting adventurous life, I always read stories in which characters came down with exotic, romantic-sounding tropical ailments. It seemed like a traveller’s badge of courage. Giardia and campylobacter, which we turned out to have acquired, may not have been quite as literary as malaria or yellow fever, but they were something. I was almost happy to be put on medication that gave my mouth a terrible metallic taste when we got home.

When the bug subsided temporarily after the attack in Selcuk, we took off north again, this time to the city of Bursa, just inland from the Sea of Marmara. Bursa, a one-time capital of the Ottomans before they completed their conquest of Constantinople, had several gorgeous mosques covered in turquoise tiles, plus a luxurious hammam that we visited to have our travel dirt scrubbed away. I’d lobbied to make it a destination because it was the starting point to hike up Uludag, a 2,500-metre mountain that was in ancient times known as an alternative Mount Olympus. From Bursa, we took a pair of cable cars to a small ski resort at about 1,600 metres. Then we set off on foot through treeless goat and sheep pastures and bare rock. It was hot and, of course, sunny. And I didn’t realize until we got there that there was a mine somewhere in the upper reaches of the mountain, which meant that scenically it left a bit to be desired. We turned back when we could see that it would be another hour of slogging in the sun past piles of mine waste. When we got back to our hotel, I noticed how much sunburn I’d picked up. Years later, when I had a basal cell carcinoma on the forehead, Rosemary accused me of giving myself cancer with “that stupid ugly hike in Turkey.”

Thanks Cheryl. Glad you're enjoying our misadventures!

That's great Elizabeth! Congratulations. Is the food reference figurative or will your book also talk about culinary adventures in your travels?