On re-reading a beloved book

My debt to Mark Helprin and my love of snow come together in 700 pages of literary magic

Re-reading a favourite book from your past is sometimes described as a reunion with an old friend. What’s not made clear in that observation is that often the old friend you encounter is the younger you.

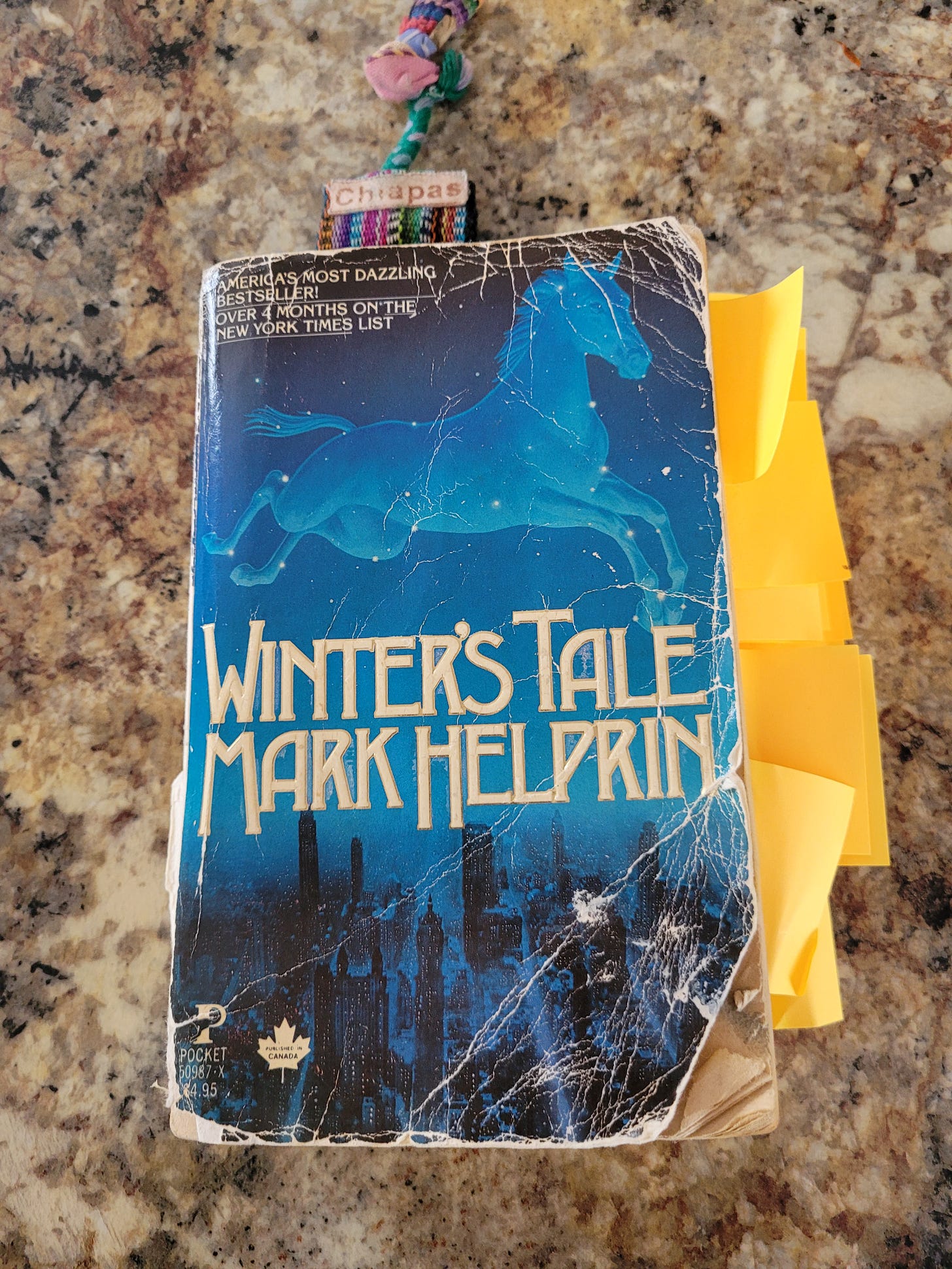

I’ve had that feeling recently while re-reading a book I devoured at age 25 and again about four years later: Winter’s Tale by Mark Helprin. In my first reading of the novel, during a summer when I was working as a park interpreter in the Alberta Rockies, I discovered a fascinating setting I’d never thought of before (the Gilded Age New York of the novel’s first section). I enjoyed a fantastical satire of the newspaper business, just a few years after my own first attempt at a journalism career. As a lovelorn young man, I soaked in the novel’s heart-on-its-sleeve romance, as Helprin depicted loves as pure as the impossibly deep snowdrifts that cover portions of the novel’s geography. When I re-read it a few years later, when I was working long hours for low pay as a small town newspaper editor and feeling cut off from friendship and connection, the novel’s themes of transformation, patience and faith buoyed me. Helprin’s cast of characters – living in a chaotic and unjust New York at the turn of the 20th century and at the turn of the 21st – offered hope that I too could find meaning and beauty in my life if I held true to my course.

Those themes struck a chord in the hearts of the novel’s early readers. Published in 1983, Winter’s Tale was a bestseller and a critical success. At nearly 700 pages, it combines elements of historical fiction, social satire, time-travelling fantasy, religious allegory and romance. It’s packed with Dickensian characters, many with Dickensian names like Reverend Mootfowl, Pearly Soames and Marcel Apand (possibly a Donald Trump caricature written even before Spy Magazine began mocking the future president as a “short-fingered vulgarian”). It features any number of magical devices, including a flying horse, a wall of cloud that swallows people up and sometimes spits them out a century later, and a magical snow-covered village hidden in Upstate New York that exists outside of normal space and time. Written while sky-high murder rates and arson sprees defined the economically struggling New York of that era, Winter’s Tale features gang warfare and apocalyptic destruction. And in the midst of all that, there’s a sort of Grail quest as a man named Hardesty Marratta sets out with a family heirloom – a kind of magical serving platter – in search of a “perfectly just city.”

You may wonder how such a grab-bag of characters, genres and plot elements could possibly hold together, but it does and I’m not the only person to think so. My old paperback edition comes with three pages of praise from writers like Joyce Carol Oates and Anne Tyler and publications ranging from People Magazine to The Village Voice (though it doesn’t, surprisingly, quote the rapturous New York Times review that concluded: “Not for some time have I read a work as funny, thoughtful, passionate or large-souled. Rightly used, it could inspire as well as comfort us. Winter's Tale is a great gift at an hour of great need.”)

It’s still a great gift and the hour is still one of great need (aren’t they all?). On this most recent reading of Winter’s Tale, I’m especially struck by how much this novel from my younger days has left an impression on me and on my writing.

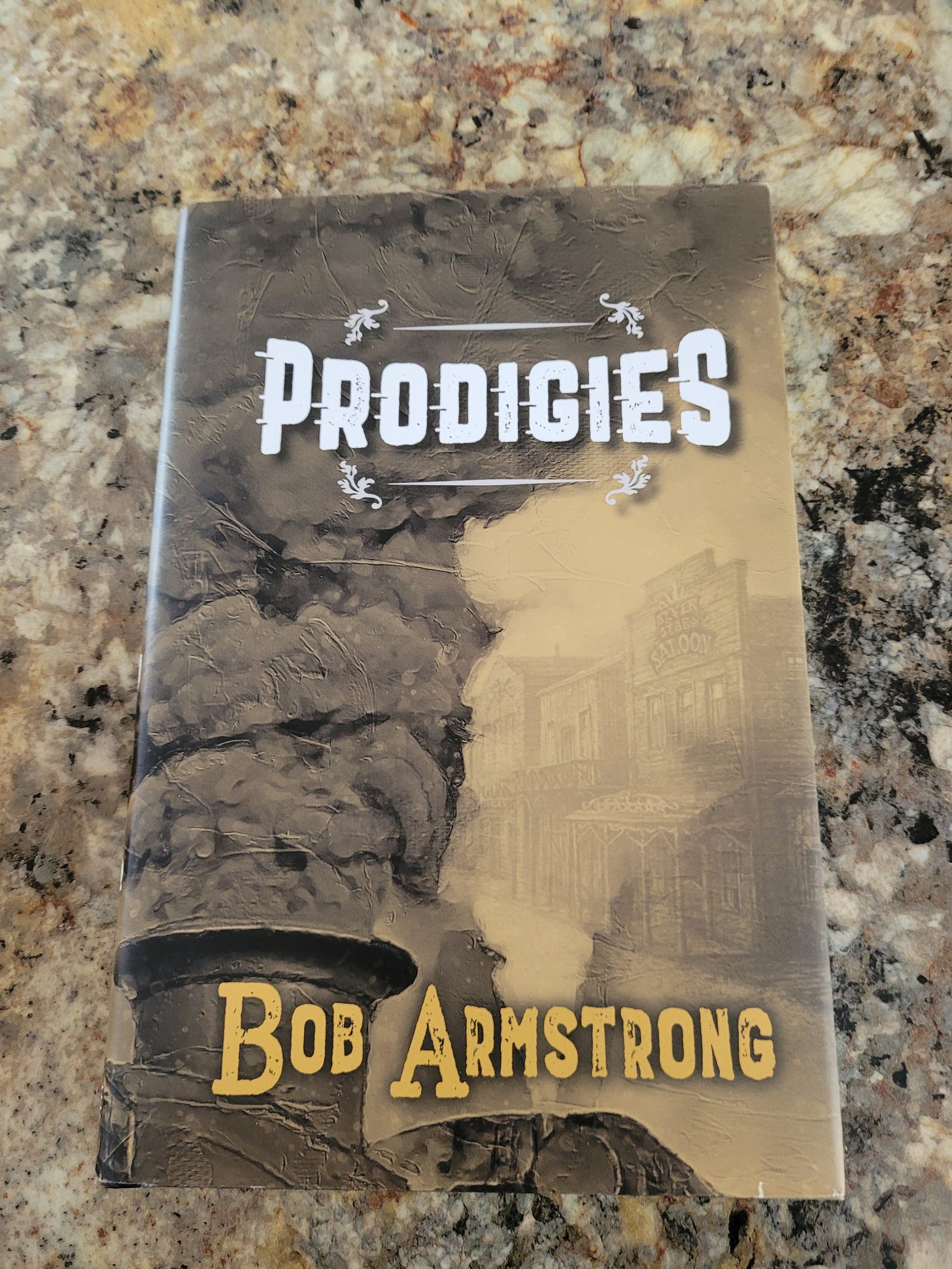

To the extent that there is one central character in such a heavily populated novel, the main character in Winter’s Tale is Peter Lake, a foundling who learns to be a master mechanic at a church-run boys’ school in late-19th century New York, is then forced into a fierce gang led by the diabolical Pearly Soames, and then falls in love with the doomed daughter of a whaler-turned-newspaper publisher. Peter Lake’s DNA shows up all through my novel Prodigies. My central character is an Irish orphan from the mean streets of Manhattan’s Five Points district who is recruited in the 1870s into a gang, then arrested and sent to a boys’ industrial school. Like Peter Lake, Daniel McCormack acquires a comic sidekick when he’s sent to reform school. While Daniel never shows Peter Lake’s astounding aptitude for mechanical work, I have given that characteristic to another of my major characters, Lincoln Henry, the mechanical-genius son of former slaves in Tennessee.

As I re-read Winter’s Tale, I keep coming across scenes that may have been stored away in my mind as inspiration for events in Prodigies. In Helprin’s novel, the questing 20th century character Hardesty Marratta finds himself caught up in an all-night poker game in the club car of a train crossing the Great Plains. In Prodigies, Daniel’s comedian friend, Segal, convinces him to try his luck in a poker game during the railroad trip from Kansas to Wyoming. In Winter’s Tale, a young Danish woman named Christiana Friebourg makes an instinctive connection with the novel’s magical flying horse. In Prodigies, an orphan (both novels are heavy on orphans) named Lily bonds just as mystically with wolves (and is pretty good with horses, too). There’s a lot of vaudeville in Winter’s Tale. In Prodigies, Lily works in a small travelling circus and we see her do a couple variations of her act.

None of this is to say that I’ve lifted language, plot points or characters from Helprin. But clearly, reading Winter’s Tale opened me up to ask certain questions and explore certain settings. It also helped me to prefer writing that is rich in image, language and detail. I’ve never been a fan of minimalism. Winter’s Tale abounds in sensory details, ornate detailing of places and people, wild weather, absurd behaviour, hellish evil, unshakeable faith, comic subplots, pathos and tragedy. I certainly don’t go as far as Helprin in my own writing, but I do sometimes find while reading my own work that I’ve taken inspiration from the heightened reality and showy prose of Winter’s Tale.

There is, in Helprin’s writing and to some extent in mine, a style that I sometimes refer to as Everything Louder Than Everything Else. (That’s the title of a song by Meatloaf, by the way.) That’s my tongue-in-cheek way of referring to writing that is the opposite of minimalism, writing that piles on the details, builds atmosphere upon atmosphere. It’s not to everybody’s taste, I’m sure, but when it works it can conjure an entire world.

Here’s Helprin, using this approach to paint the scene in which Peter Lake visits a morgue in the poorest part of New York to investigate the fate of a child he’d once glimpsed in a tenement stairwell:

“The morgue in the hospital in Printing House Square was a windowless room in a subbasement with not even an airshaft. Fifty autopsy tables stood under glaring spotlights, and on every single one a body was in repose. On some, as many as ten infants were turned sideways and lined up from one end of the table to the other like a row of disabled pistons. The corpses were of all ages and colors – men, women, children, derelicts as big as horses and as loose as a bundle of rags, muscular workers in rigor mortis, slight girls with hardly any flesh on them, criminals whose last accomplishment had been to collect a bullet hole the size of a dime, a decapitated East Indian whose head stared at its body from across the room, young children with puzzled and painful expressions, men and women who never thought it would end this way, luckless people whose last expression was surprise.”

Here’s me, using this approach to show young Daniel being taken to a cemetery in search of the grave of his vanished mother:

“They left the turnpike and trotted down to the river, which Daniel smelled long before the iron-hued water came into view. Swamp gas mixed with coal oil and creosote and beneath it all lurked a smell of death. At Mrs. Kleinschmidt’s signal, he disembarked and felt the mud suck at his feet as he walked toward a dock jutting into the water. From the weathered wooden dock, the far bank was hidden by a long finger of fog curling up the river from New York harbor. All color was drained from the scene before him. The mud, wood, water and sky were all shades of gray. Out of the fog, the prow of a ferry emerged, the sound of its churning paddle wheel breaking free of the muffling effect of the clouds, a ragged man holding onto a railing. As it approached the dock, its cargo came into focus: two wagons pulled by teams of draft horses, each piled with gleaming, brass-handled coffins.”

Have I taken more than prose stylings and images from Winter’s Tale? Perhaps. Winter’s Tale is a novel in which the storms of winter are a symbol of hope for a new and better world. In one passage, a woman remembers an intense winter storm from her childhood when the lake beside her home froze solid overnight and “it was then, as she looked over the lake, that she had learned the true meaning of the word ‘arise.’”

My chionophilia (literally, “love of snow”) may not reach the messianic extremes that Helprin does in Winter’s Tale, but I too tend to look on the arrival of a covering of snow as a time for rebirth and renewal. In the western Canadian cities and towns where I’ve lived, the year ends with a blank page, all the mistakes of the previous one erased, providing space for us to write a new year. I may not have a magical white horse, but when my skis are waxed just right and the tracks are nicely set, I can fly too.

Love your poetic-style prose.